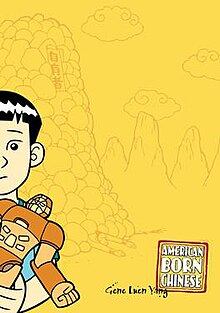

American Born Chinese is about the adolescent's struggle with finding his identity, and it is also about finding balance with his cultural identity in white America. There are plenty of things that Gene Luen Yang has spot on, such as romantic feelings and teenage angst, and there are also plenty of laughs in both his tale of young Jin Wang and the tale of the Monkey King. Jin's struggles with other people are something everyone can sympathize with. His cultural roots and Chinese appearance leaves him the butt of racial jokes. Even his well meaning teacher responds to a students ignorant comment about Chinese people eating dogs with an ignorant comment of her own: that Jin's family probably doesn't eat dogs anymore since they live in America now. With his pariah status, it is a foregone conclusion that he would become friends with the Taiwanese Wei-Chen Sun.

The story of the rebellious Monkey King, who has ambitions of being elevated to a dog, is also well-told and amusing, even if the action scenes are a bit elementary. There's a clear connection between this story and that of Jin's in that each character feels a sense of shame with their own cultural identity because it turns them into outcasts. Each character attempts to shed their ethnic identity in order to fit in. Jin changes his hair style to get a girl's attention, and the Monkey King begins wearing shoes and alters his shape to appear less monkey-like. In Yang's conclusion, though, he seems to present an either-or scenario - either one turns away from one's cultural roots, or one embraces them. There is no in-between, and there is a sense that something is sacrificed or lost no matter what choice is made. In embracing his cultural roots, the Monkey King becomes docile rather the enjoyably rebellious and ambitious individual of the first part of his story. And Jin must choose whether to be wholly Asian or white, rather than adapting to both cultures.

There is a third story here, about Chin-kee, the distant cousin of the white American, Danny. The Chin-kee story appears satirical at first glance, with a laugh track appearing anytime Chin-kee enacts one of his many cultural stereotypes. Chin-kee is not just a satire of the stereotypical outsiders might have of a Chinese citizen, but he is also how people like Jin fear that others view them. So in a way, Chin-kee could be seen as an internal conflict. The way that Yang merges these three stories breaks some of the magic, since two of these stories are clearly fantastical, while one is realistic - so they don't merge particularly well or believably. As entertaining and truthful as much Yang's novel is, I find that falters in its conclusion.

No comments:

Post a Comment